Much has been written about China's economic miracle. Lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty into the middle class in a single generation is a feat unprecedented in human history. The recent claim of having eliminated extreme poverty, if valid, is another remarkable milestone.

China continues to grow, and its current efforts to address the inequalities created by its past decades of uneven growth are worth watching. If successful, it would be a model worth emulating by the rest of the world, especially since the failures of both Communism and Capitalism have by now become obvious. "Socialism with Chinese characteristics" may be the economic model of the future.

It's a well known fact that over the past forty years since Deng Xiaoping's economic liberalisation, the provinces on China's eastern seaboard have developed at a much faster pace than the interior. The inequalities in wealth between urban and rural regions, and between coastal and interior provinces, have become a source of potential social conflict, one which the Chinese government is anxious to address. The Belt and Road Initiative is a means to provide better connectivity to interior provinces and thereby spur their development over the next thirty to forty year period. As this wonderfully insightful article by the Lowy Institute describes, there are several drivers, both internal and geo-economic, for the BRI, and if that initiative succeeds, it would have solved more than one problem at the same time.

As one who has studied China with great interest over the past few years, I believe that a crucial element of the country's development strategy is a certain technology, one that has hitherto never been deployed on such a scale anywhere in the world.

That technology is high-speed rail (HSR), and the Chinese government is betting on the multiplier effect that it will have on its economy.

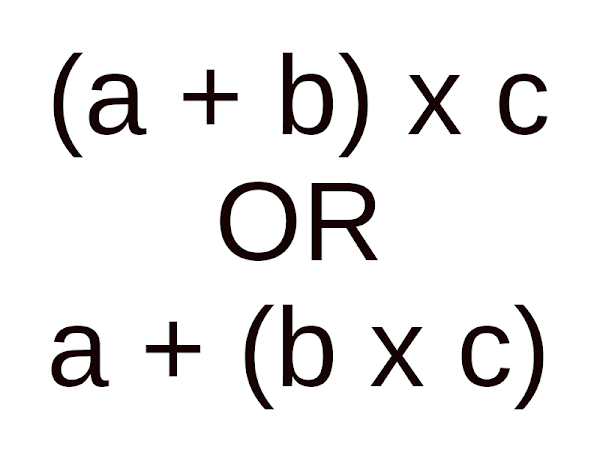

Upon some analysis, I believe this expectation is justified. I created this simple chart to explain why.

There has traditionally been a speed-economy trade-off in the transport sector. Airplanes can get people and goods from place to place faster than any other mode of transport, but air travel is not cheap. At the other end of the scale, trains (and other modes of bulk surface transport) are affordable, but take much longer to connect places together.

Economists often draw a line to indicate the trade-offs inherent in a given portfolio of choices. In investment finance, such a line is called an "efficient frontier". In this chart of the transport sector, the efficient frontier could be thought of as representing a certain generation of technology.

What high-speed rail does is shift the efficient frontier outwards. High-speed rail is emphatically not on the old efficient frontier defined by the existing options of surface and air transport. High-speed rail is much faster than conventional surface transport, and much cheaper than air transport. While it's not quite the best of both worlds (i.e., as fast as air transport and as cheap as conventional rail), it is still a sufficient advancement to represent the next generation in transportation technology, one whose enhanced efficiency can rejuvenate slowing economic growth.

[Even this can change in the near future. The first-generation HSR 和谐号 héxié hào (Harmony) was capable of 350 kmph (operating speed 280 kmph). The second generation 复兴号 fùxīng hào (Rejuvenation) touched 420 kmph (operating speed 350 kmph). Future generations of HSR will probably start to approach aircraft speeds, and at far lower costs. High-speed rail would then be clearly superior to air travel with no trade-off at all.]

I believe that thanks to the aggressive rollout of high-speed railway lines throughout the country (a planned doubling of track length by 2035), the Chinese economy, far from slowing down, is going to continue to grow at a high rate for many years into the future. The less developed interior provinces, specifically Xinjiang, Tibet, Gansu, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Qinghai, Sichuan and Yunnan, which have hitherto not had high-speed rail connectivity, will see a boost to their economic growth.

If I were a student of economics wishing to do a doctorate in the area of developmental economics, I cannot think of a more exciting topic than the study of how high-speed rail acts as an economic multiplier to spur growth, and additionally, as a means to balance that growth by pulling far-flung regions into a tighter economic sphere.

High-speed rail is China's secret weapon that can enable it to leapfrog the West in prosperity within 10 to 15 years. The technology has the potential to (1) sustain China's breakneck pace of growth and avoid the "middle-income trap", (2) alleviate the imbalance in regional development and solve the problem of widening inequality that other countries are struggling with, and (3) make China a much more efficient and competitive economic engine, entrenching it in every other's nation's economy.