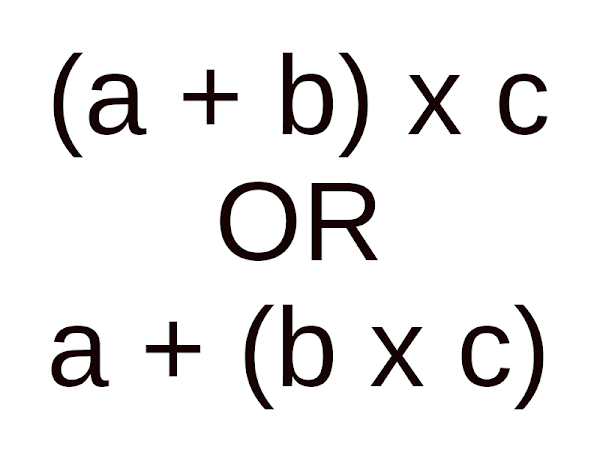

A sentence I recently came across on Duolingo confused me for a while, until I realised there was a very simple and basic rule that I should have used to interpret it. It's like knowing where the brackets go when evaluating a mathematical expression.

But before I talk about the sentence, let me provide an advance hint about the grammatical rule I should have used.

There are two ways a question can be posed in Chinese. One is with the toneless 吗 ma particle at the end of an assertive statement, the other is by immediately following the verb by its negative.

Example:

1. 你 是 中国人 吗?nǐ shì zhōngguórén ma? ("Are you Chinese?", literally "You are Chinese person (question particle)")

2. 你 是不是 中国人? nǐ shìbùshì zhōngguórén? ("Are you Chinese?", literally "You are-not-are Chinese person")

Another example:

1. 你 有 钱 吗?nǐ yǒu qián ma? ("Do you have money?", literally "You have money (question particle)")

2. 你 有没有 钱?nǐ yǒuméiyǒu qián? ("Do you have money?", literally "You have-not-have money")

Remember these two styles of asking a question as I tell you about the sentence I came across on Duolingo.

有没有风险的投资吗?yǒu méiyǒu fēngxiǎn de tóuzī ma?

风险 fēngxiǎn means "risk", and 投资 tóuzī means "investment".

Duolingo's translation was "Is there a risk-free investment?"

I was puzzled. To my mind, this seemed to be asking the very opposite question, "Is there or is there not a risky investment?"

After a long time scratching my head, I realised that I was placing the "brackets" wrongly around the words in this sentence.

This is what I was doing, and I was wrong.

(有没有) (风险 的 投资) 吗?(yǒuméiyǒu) (fēngxiǎn de tóuzī) ma? ("Is there a risky investment?", literally "(Have-not-have) (a risky investment) (question particle)")

But the presence of the 吗 ma at the end should have alerted me to the rule that this was the first style of question, not the second. If languages could use brackets like mathematics, that would be a good way to show which words need to be grouped together. This was how I should have used the "brackets" on this sentence:

有 [ (没有 风险 的) 投资 ] 吗?yǒu [ (méiyǒu fēngxiǎn de) tóuzī ] ma? ("Is there an investment not having risk?", literally "Have a [ (not-have-risk) investment ] (question particle)")

In other words, the correct way to parse this sentence is not "Have you or have you not a risky investment?" but "Have you an investment not having risk?". The "have not" refers to the investment having a risk, not to the broker having such an investment.

What at first seemed to be a confusing sentence turned out to make perfect sense. I had simply forgotten a very basic rule I had learnt early on.

But what if I had in fact wanted to ask if there was a risky investment?

Why, then I should simply drop the 吗 ma from the end of the sentence! Then the 有没有 yǒuméiyǒu ("Have-not-have") would go together.

2. 有没有 风险 的 投资?yǒuméiyǒu fēngxiǎn de tóuzī?

In other words, this would be (有没有) (风险 的 投资)?(yǒuméiyǒu) (fēngxiǎn de tóuzī)? ("Is there a risky investment?", literally "Have-not-have risky investment")

Or I could use the simpler first style, keeping the 吗 ma and dropping the negative-verb 没有 méiyǒu.

1. 有 风险 的 投资 吗?yǒu fēngxiǎn de tóuzī ma? ("Is there a risky investment?", literally "Have risky investment (question particle)")

No comments:

Post a Comment